Every startup has its own natural level of startup costs. It’s built into the circumstances, like strategy, location, and resources. Call it the natural startup level; or maybe the sweet spot.

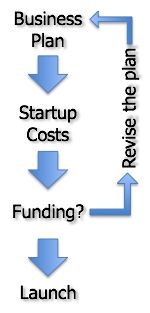

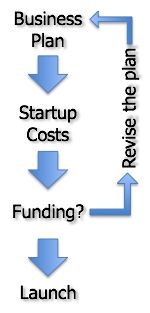

1. The Plan

For example, Mabel’s Thai restaurant in San Francisco is going to need about $950,000, while Ralph’s new catering business needs only about $50,000.  The level is determined by factors like strategy, scope, founders’ objectives, location, and so forth. Let’s call it its natural level. That natural startup level is built into the nature of the business, something like DNA.

The level is determined by factors like strategy, scope, founders’ objectives, location, and so forth. Let’s call it its natural level. That natural startup level is built into the nature of the business, something like DNA.

Startup cost estimates have three parts: a list of expenses, a list of assets needed, and an initial cash number calculated to cover the company through the early months when most startups are still too young to generate sufficient revenue to cover their monthly costs.

It’s not just a matter of industry type or best practices; strategy, resources, and location make huge differences. The fact that it’s a Vietnamese restaurant or a graphic arts business or a retail shoe store doesn’t determine the natural startup level, by itself. A lot depends on where, by whom, with what strategy, and what resources.

While we don’t know it for sure ever — because even after we count the actual costs, we can always second-guess our actual spending — I do believe we can understand something like natural levels, somehow related to the nature of the specific startup.

Marketing strategy, just as an example, might make a huge difference. The company planning to buy Web traffic will naturally spend much more in its early months than the company planning to depend on viral word of mouth. It’s in the plan.

So too with location, product development strategy, management team and compensation, lots of different factors. They’re all in the plan. They result in our natural startup level.

2. Funding or Not Funding

There’s an obvious relationship between the amount of money needed and whether or not there’s funding, and where and how you seek that funding. It’s not random, it’s related to the plan itself. Here again is the idea of a natural level, of a fit between the nature of the business startup, and its funding strategy.

It seems that you start with your own resources, and if that’s enough, you stop there too. You look at what you can borrow. And you deal with realities of friends and family (limited for most people), angel investment (for more money, but also limited by realities of investor needs, payoffs, etc.), and venture capital (available for only a few very high-end plans, with good teams, defensible markets, scalability, etc.).

3. Launch or Revise

Somewhere in this process is a sense of scale and reality. If the natural startup cost is $2 million but you don’t have a proven team and a strong plan, then you don’t just raise less money, and you don’t just make do with less. No — and this is important — at that point, you have to revise your plan. You don’t just go blindly on spending money (and probably dumping it down the drain) if the money raised, or the money raisable, doesn’t match the amount the plan requires.

Revise the plan. Lower your sites. Narrow your market. Slow your projected growth rate.

Bring in a stronger team. New partners? More experienced people? Maybe a different ownership structure will help.

What’s really important is you have to jump out of a flawed assumption set and revise the plan. I’ve seen this too often: you do the plan, set the amounts, fail the funding, and then just keep going, but without the needed funding.

And that’s just not likely to work. And, more important, it is likely to cause you to fail, and lose money while you’re doing it.

Repetition for emphasis: you revise the plan to give it a different natural need level. You don’t just make do with less. You also do less.

The sun beamed in the patio outside my office. We talked about Palo Alto Software and its web subsidiary bplans.com. At one point the VC said:

The sun beamed in the patio outside my office. We talked about Palo Alto Software and its web subsidiary bplans.com. At one point the VC said:

I say let the nature of the business, and the goals of the entrepreneur, determine the financial strategy regarding investment. Some businesses simply can’t sprout without healthy amounts of outside investment. Others have no good reason to even think of investment. And most are in between, with investment a matter of what the owners ultimately want. And there is what I’ve called the

I say let the nature of the business, and the goals of the entrepreneur, determine the financial strategy regarding investment. Some businesses simply can’t sprout without healthy amounts of outside investment. Others have no good reason to even think of investment. And most are in between, with investment a matter of what the owners ultimately want. And there is what I’ve called the  For example, a plan calls for $3 million investment for 2010 and its projected cash balance at the end of 2010, and again at the end of 2011, never goes below $2.5 million.

For example, a plan calls for $3 million investment for 2010 and its projected cash balance at the end of 2010, and again at the end of 2011, never goes below $2.5 million. In

In  But my beef with Jason’s rant is his total lack of distinction between thousands of dollars as a pay-to-pitch fee, charged by for-profit middle-men companies, and the normal fees of tens or hundreds of dollars charged by angel investment groups as part of the pitching process. That’s like apples and oranges. And the oranges are getting smeared with the bad apples.

But my beef with Jason’s rant is his total lack of distinction between thousands of dollars as a pay-to-pitch fee, charged by for-profit middle-men companies, and the normal fees of tens or hundreds of dollars charged by angel investment groups as part of the pitching process. That’s like apples and oranges. And the oranges are getting smeared with the bad apples.

You must be logged in to post a comment.