It’s an obvious question. And if you’re looking for startup investors you’d better be able to answer it well, and quickly too. No wandering eyes. No doubt. If you’re doing a pitch, have a slide for it. And be specific.

I liked this from Ben Yoskovitz’s Instigator Blog on Use of Funds:

…most descriptions of “use of funds” are incredibly generic and standard, typically involving the following: hire key personnel, product development, sales & marketing. Hhhm…the phrase, “No shit Sherlock…” comes to mind.

And on the other hand, there’s this about that, from Perfecting Your Pitch, by Guy Kawasaki’s Garage.com Ventures:

It should be clear from your financials what your capital requirements will be. On this slide you should outline how you plan to take in funding—how big each round will be, and the timing of each—and map the funding against your key near-term and medium-term milestones. You should also include your key achievements to date. These milestones should tie to the key metrics in your financial projections, and they should provide a clear, crisp picture of your product introduction and market expansion roadmap. In essence, this is your operating plan for the funds you are raising. Do not spend time presenting a “use of funds” table. Investors want to see measures of accomplishment, not measures of activity.

So go figure. There are two opposite points of view from two good sources.

I’m amazed, meanwhile, how often I see people pitch startups to investors without having a good answer to that question. I expect an instant answer, without hesitation, and if it’s a slide deck there should be a slide.

And that doesn’t mean that anybody necessarily believes what you say. It’s all educated guessing. But details add credibility. And if you can’t answer that question, what do you think your audience is thinking?

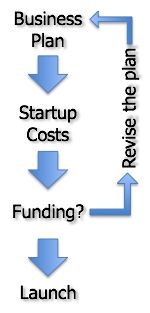

There is a standard way to calculate starting costs.

- Make a list of the stuff you need to purchase before you start. Include expenses like early salaries, cleaning up the location, developing the website, packaging if relevant, prototypes … it’s a collection of educated guesses, of course. It’s just guessing, but how can you not do it?

- Do your projected first year cash flow. Estimate sales, costs, expenses, and payment lags from business customers, your own lags paying your vendors, plus what you need in inventory. If this isn’t a cash deficit, recalculate. In real startups it almost always is.

- Add those startup costs with the deficit spending, and that’s what you need from investors.

- Reality check: if that calculated amount is way too much, investors will laugh at you, go back and change your plan. Spend less. Look for the startup sweet spot.

- Double reality check: if you can spend less, maybe you can do it without investors. There are other ways to get money. But even in that case, don’t you want to have a good idea of what it takes?

- Triple reality check: if you’ve got a high-end high-tech startup, looking for serious angel or VC investors, give them a break and show spending the money on things that make for growth, excitement, virality, sizzle. If you don’t know what that is, rethink your plan.

(Image: mgkaya/istockphoto.com)

The level is determined by factors like strategy, scope, founders’ objectives, location, and so forth. Let’s call it its natural level. That natural startup level is built into the nature of the business, something like DNA.

The level is determined by factors like strategy, scope, founders’ objectives, location, and so forth. Let’s call it its natural level. That natural startup level is built into the nature of the business, something like DNA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.