A good argument for teams in business is not having to know finance if you love sales, marketing, or product development. But you’re a business owner. You’ll run your business better if you understand the standard business plan financials. These important terms aren’t that hard to learn and understand. You owe it to yourself and your business.

Like it or not, some very common terms including capital, assets, liabilities, costs, and expenses have very exact meanings in accounting and finance; but they are often used in conversation with much more flexible and fuzzy meanings. For example, in a conversation over coffee, a business owner might refer to her website as an asset; but in finance it’s an expense. And an employee whose work is sloppy might be called a liability; but that’s not proper use of the accounting term.

Just Six Terms

Every item in every standard accounting system is one of the following six terms. The first three (assets, liabilities and capital) appear on a standard balance sheet, and the next three (sales, direct costs, and expenses) appear on the standard income statement. Explanations of those, plus the all-important cash flow, are coming. But first, the six terms you need:

Assets

Assets are things of value a company owns. Money is an asset. Money in a bank account, or in securities like stocks and bonds, or liquidity accounts and banking instruments, is an asset. It goes on your books as some amount of dollars or pounds, francs, yen, or whatever currency you use. Land, buildings, production equipment, and furniture are assets. One definition is “anything with monetary value that a business owns.” Inventory is a very common category of assets, meaning the goods a business owns to resell (like the books in a bookstore or the bicycles in our cycle shop example), or, in a manufacturing business, materials to be assembled or processed to become a product.

Assets are often divided into current or short-term assets and fixed or long-term assets. The exact distinction between the two usually depends on decisions a company makes and sticks to consistently over time. Land and buildings are durable production equipment are almost always fixed or long-term assets, and furniture and inventory are almost always short-term assets. Some companies consider vehicles long-term assets, and some consider them short-term assets; and some vehicles (dump trucks and cement mixers, for example) are almost always long-term assets. You have flexibility on how you categorize long- and short-term as long as you know it and stick to it.

Assets can be tangible, like money in banks or physical goods, or intangible, like patents and trademarks and money owed to you, called Accounts Receivable.

Tax law and accepted standards dictate the value of the assets listed in your books. This can be annoying when your accounting lists a piece of land at $100,000 because that’s what you paid 10 years ago, even though its market value is $500,000 today. And tax code makes you list your patents and trademarks in your books at the value of the legal expenses you incurred in securing the registration; less “amortization,” a complicated formula that specifies in tax code the decline in value over time. And your plant, equipment, and vehicles have to be listed at what you paid for them less “depreciation,” another complicated formula that tax code specifies for their hypothetical decline in value.

Liabilities

Liabilities are debts: money your business owes and has to pay back. The most common liability is called Accounts Payable, which can be any money you owe to anybody but is usually money owed to vendors for goods and services purchased recently but not yet paid for. And there are notes, loans outstanding, long-term loans, and others.

Like assets, liabilities are often divided into short-term or long-term, and short-term liabilities are often called current liabilities. Accounts Payable are always short-term or current liabilities. Companies can choose how to distinguish between short- and long-term liabilities, as long as they are consistent. So some companies call debts owed within a year short-term debts, and others call them current debts. Some companies break out the next year’s payments of long-term debts as “Current Portion of Long-term Debt.” All of these options are fine as long as you maintain them consistently.

Capital

The quickest way to explain capital is by the magic formula that is always true in finance and accounting:

Capital = Assets less Liabilities

Capital starts formally with money the owners of a business put into its bank account to get it started. When our restaurant example owner Magda writes a check from her own funds to open a bank account for her restaurant, that’s supposed to go into the books as capital. It’s usually called paid-in capital. When an angel investor writes a check to a startup, that money goes into the books as paid-in capital.

You’ll also hear about so-called working capital, which is the money it takes to keep a company afloat, making payroll, buying inventory, and waiting for business customers to pay what they owe. Accountants and financial analysts calculate working capital by subtracting current or short-term liabilities from current or short-term assets.

And retained earnings, which are profits you didn’t distribute to yourself or other owners as dividends, or to yourself or other co-owners as a draw, add to capital in standard accounting. If there are no dividends, then last year’s earnings in the balance sheet are added to previous Retained Earnings to calculate this year’s Retained Earnings. And both Earnings and Retained earnings are part of capital, while dividends and distributions or draws decrease capital.

But none of those common interpretations of capital change the basic rule. The capital in a business is always, exactly, in every case, the number that results from subtracting the liabilities from the assets.

Sales

Most of us understand sales from an early age. Sales is exchanging goods or services for money. Technically, in standard accounting, the sale happens when the goods or services are delivered, whether or not there is immediate payment. Do you know it can be a criminal offense to report financial results including sales that you haven’t actually made, even if you are 99% sure your client intends to buy? Some very big companies have gotten into legal trouble for confusing optimism with actual sales, when for example they book a full year’s service contract into sales in the same month the customer signed the agreement. Technically the sale is for 1/12th of the annual contract value each month.

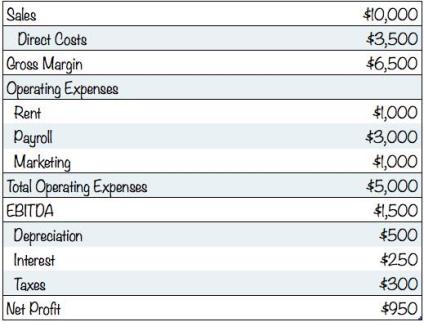

Direct costs (COGS, unit costs, cost of sales)

Most people learn COGS in Accounting 101. That stands for Cost of Goods Sold, and applies to businesses that sell goods. COGS for a manufacturer include raw materials and labor costs to manufacture or assemble finished goods. COGS for a bookstore include what the storeowner pays to buy books. COGS for Garrett, our bicycle shop owner in Section 3, are what he paid for the bicycles, accessories, and clothing he sold during the month. Direct costs are the same thing for a service business: the direct cost of delivering the service. So for example it’s the gasoline and maintenance costs of a taxi ride.

Direct costs are different down the value chain of a business. The direct costs of a bookstore are its COGS, what it pays to buy books from a distributor. The distributor’s direct costs are COGS, what it paid to get the books from the publishers. The direct costs of the book publisher include the cost of printing, binding, shipping, and author royalties. The direct costs of the author are very small, probably just printer paper and photocopying; unless the author is paying an editor, in which case the editor’s income is part of the author’s direct costs.

The costs of manufacturing and assembly labor are always supposed to be included in COGS. And some professional service businesses will include the salaries of their professionals as direct costs. In that case, the accounting firm, law office, or consulting company records the salaries of some of their associates as direct costs.

Direct costs are important because they determine Gross Margin. Gross Margin, which is part of the Profit and Loss, is an important basis for comparison with other companies.

Expenses

It’s hard to define expenses because we all have a pretty good idea. Expenses include rent, payroll, advertising, promotion, telephones, Internet access, website hosting, and all those things a business pays for but doesn’t resell. They are amounts you spend on business goods and services that aren’t direct costs but reduce your taxable income and profits.

You have to understand what isn’t an expense. Repaying loan principle isn’t an expense. Buying an asset isn’t an expense. Purchasing inventory isn’t an expense; amounts spent on inventory go into direct costs when goods are sold, but they aren’t expenses.

(Ed note: this is reposted here from the original at leanplan.com.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.