This is the latest post in my series on standard business plan financials. I’ve already written about the three essential projections, and how to do each, plus posts on standard vocabulary, timeframes, and so on. This one covers some common misunderstandings and errors that occur.

The area of financial analysis is one in which definitions matter a great deal. This area is full of terms, such as “assets” and “expenses,” that have specific meaning in accounting and finance that is much more carefully defined that what we have in general business discussion. A great logo or excellent brand history might be called an asset in a general way, and in a general sense, they both are – but neither are assets in a strict accounting and finance context.

So this post is to help with these common misconceptions. I don’t particularly like the way the area of finance and accounting demands specific meanings, but for standard business plan financials, this is important.

Profit and Loss is Also Called Income

The two phrases have the same meaning. An Income Statement, or Projected Income, is exactly the same as a Profit and Loss Statement, or Projected Profit and Loss. Too bad both exist because every time I write about them I always have to clarify. Now you know.

Cash vs. Profits

This is critical. I covered this basic concept in this list of top business plan mistakes in and in several other posts on this blog, because it’s important. However, I can’t do this list without starting with this very big one. It’s one of the most dangerous misunderstandings in business. Profitable companies can run out of money, and fail. It happens, for example, when an important customer stops paying in time and there isn’t enough working capital. Or when too much money is invested in inventory.

If you have a business that sells only for cash, credit card, or checks, then the cash flow implications of sales on credit and accounts receivable don’t affect you. If you don’t make, distribute, or resell products, then the cash flow implications of inventory don’t affect you. If you have a very simple cash flow, then profits are pretty close to cash. If you don’t, watch that difference very carefully. Profits are an accounting fiction. You spend cash, not profits.

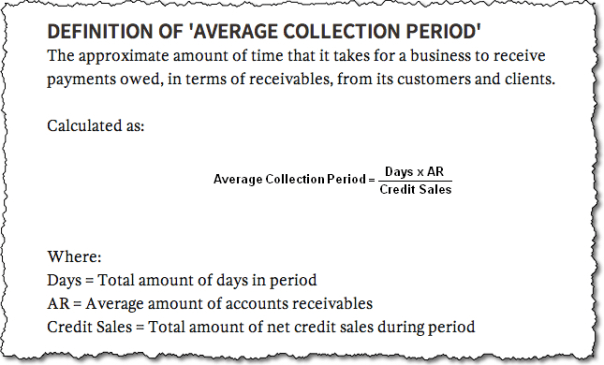

Understand sales on credit and accounts receivable. When your business sells anything to another business, you usually have to deliver an invoice and wait to get paid. That’s called sales on credit, which has nothing to do with credit cards, but plenty to do with B2B sales. When you make the sale and deliver the invoice, the invoice amount increases sales and accounts receivable. When that money gets paid, it decreases accounts receivable and increases cash.

Assets vs. Expenses

Although many accounting and financial definitions are rigid, use and application aren’t. Much depends on interpretation and application.

For example, take development expenses. As you pay a construction company to build a new building for your business, you are buying an asset. What you pay is not deductible as an expense. But when a software business pays programmers to build a new software product, that company is spending on an expense, not an asset. Lines of programming code aren’t normally assets. Nor is a product design, packaging design, or a prototype. Those are expenses.

Who decides these things? The government does, in tax code. A smart business owner would prefer to book every dollar spent as either direct cost or business expense, because that would reduce taxable income and mean more money in the bank. Tax law decides what you can call an expense and what has to be booked as an asset.

So U.S. federal tax code makes buying office equipment an expense, at least up to an annual limit that changes, but has been more than $100,000 for several years now. That’s good for businesses because they can buy computers, phones, and other office equipment and deduct the cost from taxable income. But it’s odd because logically that’s buying assets, so it should increase the sum of the assets and not affect the profits or taxes. And you could choose to book those computers as assets, if you’d rather show higher profits on your books, and more assets, but have less money.

Costs vs. Expenses vs. Inventory

In the earlier post Six Key Terms I made the distinction between direct costs and expenses. Direct costs are also called COGS for Cost of Goods Sold and unit costs. These are costs that happen only if the business makes a sale, such as the cost of the bicycles our bike storeowner sells, or the cost of gasoline used by the taxi. Although the distinction between costs and expenses makes no difference to the profits in the bottom line, we use this distinction to calculate Gross Margin. Gross Margin is sales less direct costs. It is a useful basis of comparison between different industries and between companies within the same industry. Furthermore, the direct costs number helps in understanding variable costs and fixed costs, which is another useful analysis in itself, and it’s the core of a break-even analysis as well.

The distinction isn’t always obvious. For example, manufacturing and assembly labor are supposed to be included in direct costs, but factory workers are sometimes paid even when there is no work. And some professional firms put lawyers,’ accountants,’ or consultants’ salaries into direct costs. These are judgment calls. When I was a young associate in a brand-name management consulting firm, I had to assign all of my 40-hour work week to specific consulting jobs for cost accounting.

When in doubt, remember that consistency is the rule. Whichever way you do it, stick to it over time.

Depreciation and Amortization

Depreciation is something you learn once and it usually sticks. Most business owners understand it. Tax codes and accounting standards prevent business owners from deducting the cost of business assets such as a vehicle, a building, office furniture, or land when you buy them. We’d all prefer to call those things expenses because they reduce our taxable income and therefore our taxes; but we can’t. So our consolation prize is that we get to depreciate them, and depreciation is an expense that reduces taxable income.

The practical result is that any business owning assets has depreciation as an expense. Tax code specifies formulas for depreciation based on the type of asset, but as a simple example, assume you can deduct one-fifth of the purchase price of a business vehicle every year for five years. That deduction is depreciation. The book value of the asset starts at the purchase price, and declines by one fifth every year for five years. At the end of the five years, the book value is zero, so if you sell the vehicle, the entire sales price is profit. Profit is based on book value, for tax purposes.

Depreciation shows up as an expense even though it doesn’t actually cost money. The asset did cost money, but that went somewhere else in your books, not into profit and loss.

Most people count depreciation as an operating expense, but some don’t.

Amortization is depreciation’s sidekick, which works like depreciation but applies to assets like legal expenses, which weren’t really assets anyhow (it’s tax law — don’t try to understand; just be aware of it.) You can also think of it essentially as depreciation of intangible assets, like intellectual property, or so-called goodwill.

EBIT vs. EBITDA

The classic Profit and Loss includes EBIT, which stands for Earnings Before Interest and Taxes. Lately EBITDA has become more fashionable. The DA in EBITDA stands for “depreciation and amortization” and the EBIT is the same EBIT, so EBITDA is probably a more useful term because of the nature of depreciation and amortization.

Timing is Very Important

As I explained in What’s Accrual Accounting and why does it matter, accrual accounting gives you a more accurate financial picture, unless you’re very small and do all your business, both buying and selling, with cash only. I know that seems simple, but it’s surprising how many people decide to do something different. And the penalty of doing things differently is that then you don’t match the standard, and the bankers, analysts, and investors can’t tell what you meant.

Your Profit and Loss depends on timing. It’s supposed to show financial performance over some specified period of time, like a month or a year. What you call sales on that statement is supposed to be sales made during that period. The goods changed hands or the services were delivered. When you were paid for it, and when you originally bought what you sold, is supposed to be irrelevant.

Therefore, the direct costs are supposed to be the costs of the items or services reported as sales during that period.

So when a bike storeowner buys a bicycle he wants to sell, the money he spent on it remains in inventory until he sells it. It goes from inventory (an asset) to direct costs for the income statement in the month when it was sold. If it is never sold, it never affects profit or loss, and remains an asset until some day when the accountants write off old never-sold obsolete inventory, at which time its lowered value becomes an expense. In that case, it was never a direct cost.

Expenses have timing issues too. If you contract a television advertisement in October, and it appears in December, then it should go into the December Profit and Loss. And that’s true even if you end up paying for it in February. The idea is that sales, direct costs, and expenses go into the month they happen.

Additional Details

- Tax law allows businesses to establish so-called fiscal years instead of calendar years for tax purposes. For example, your fiscal year might go from February through January, or October through September. Use “FY” (as in “FY07”) to specify the year in your plan. The year is always the calendar year in which a plan ends, not the year it starts.

- Don’t call your investment venture capital unless it comes from one of the few hundred actual VC firms. If you’re getting venture capital, you’ll know it. If not, just call it investment.

- Pro forma is just a dressed up way to say projected or forecast. It’s one of those potentially daunting buzzwords that really isn’t complicated. The pro forma income statement, for example, is the same as the projected profit and loss or the profit and loss forecast.

I think product/market fit, defensibility, scalability, market need and management experience are much harder to fix than bad financials. A good business with poor financial projections will survive and grow.

I think product/market fit, defensibility, scalability, market need and management experience are much harder to fix than bad financials. A good business with poor financial projections will survive and grow. For example, a plan calls for $3 million investment for 2010 and its projected cash balance at the end of 2010, and again at the end of 2011, never goes below $2.5 million.

For example, a plan calls for $3 million investment for 2010 and its projected cash balance at the end of 2010, and again at the end of 2011, never goes below $2.5 million.

You must be logged in to post a comment.